Hexagram 12 – Blocked?

‘Blocking it, non-people.

Noble one’s constancy bears no fruit.

Great goes, small comes.’

Hexagram 12, the OracleHowever clearly we understand that there are no ‘bad’ hexagrams, we’re probably not over the moon when we cast Hexagram 12. It’s at least nice to be able to think that, if we could come up with some ‘noble one’s constancy’, it would bear fruit.

And yet… that feeling of stasis, frustration and head-meet-brick-wall futility are strongest when 12 is unchanging – Blocked with nowhere to go. When lines are moving, it tends to be about shifting the block – one way or another, with more or less success – much as Hexagram 18 tends to be about dealing with Corruption. 12’s moving line texts are lively and rich with imagery. For instance…

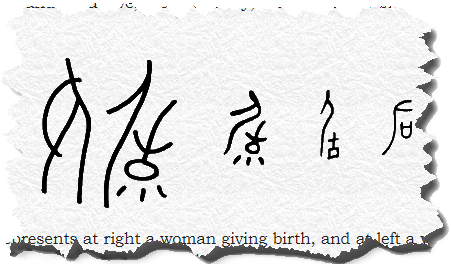

Bao 包, embracing

…bao 包, ’embracing’, in lines 2 and 3:

‘Embracing the charge.

Small people, good fortune.

Great people, blocked. Creating success.’

Hexagram 12, line 2‘Embracing shame.’

Hexagram 12, line 3The word means enveloping, enwrapping, encompassing, and also undertaking something – wrapping yourself round it, as it were, and making it your responsibility.

Hence in 12.2, ’embracing the charge’ has to do with accepting a task, internalising an order. As I put it, going on for 10 years (!!?!) ago:

“You are offered an agreement like a contract, with its own set of mutual expectations, requirements and compensations. To embrace it is to accept the terms you are given, and enter into their service – something which has an utterly different significance for small and great people.”

Commentary on 12.2 from I Ching, Hilary BarrettLine 3 describes someone taking on and internalising shame in a similar way:

“You feel shame, and carry it enfolded within you, as part of yourself – whether or not you’re fully aware of its influence. Since you don’t feel entitled to anything much, you draw back into yourself and don’t feel able to ask directly for what you want or need.”

Commentary on 12.3 from I Ching, Hilary Barrett You can get more of a feel for this one by looking at its position in the trigram-picture as a whole. Line 3’s just inside the threshold between inner and outer trigrams, looking (and leaning, and sometimes hankering) outward. But here, heaven’s above earth and moving away, and so as line 3 looks out across the threshold, it feels how the gap is widening. It curls inward around its sense of inadequacy, of being small, and Retreats – but also wants to reach out with an offering in expiation (another meaning of ‘shame’).

The etymology of bao is very simple: it shows a foetus in the womb.

(That casts a whole new light on ‘great goes, small comes,’ doesn’t it?)

And here’s the Easter egg: when 12’s two bao lines change, they show Hexagram 44, Coupling behind them:

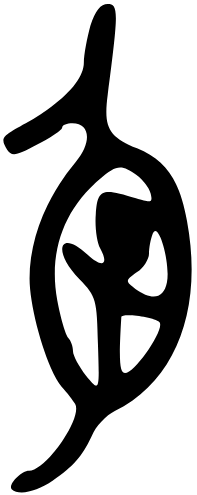

That’s Hexagram 44 whose name shows a woman giving birth – see LiSe’s site for more:

And, of course, Hexagram 44 has its own rich fertility imagery, with the wrapped (bao) fish and melon.

Blocked with bao-enwrapping means Coupling and birth.

One more wrapper…

Hexagram 12 has one more instance of bao, hidden away in line 5:

‘Resting when blocked.

Great person, good fortune.

It is lost, it is lost!

Tie it to the bushy mulberry tree.’

Hexagram 12, line 5The hidden bao character here is the word translated as ‘bushy’. It’s written with the same foetus-in-the-womb element, plus the ‘plant’ radical: 苞. We can imagine that a bushy mulberry is one that wraps and contains, womb-like.

Such imaginings are not too academically respectable – but on our way back to respectability, let’s take a detour via the story of the birth of Yi Yin:

A woman who lived near the Yi River was warned in a dream that when she saw her mortar leaking water, she should flee to the east and not look back.

This happened the very next day, so she warned her neighbours and fled east as she’d been told. But after ten leagues, she looked back, seeing how her town had completely disappeared beneath the floodwaters – and she was transformed into a hollow mulberry.

Later, when a local woman came gathering mulberry leaves for the silkworms, she found the baby Yi Yin inside the tree.

Of course, bao means ‘enwrap, embrace’, not ‘pregnancy’. Still… the Yijing is poetry; it has layers.

And speaking of those layers – changing all three bao lines of Hexagram 12 leads to Hexagram 50: the great Vessel, the ultimate container.

*Easter egg?

(*That’s ‘Easter egg’ in the painfully geeky sense as defined by Wikipedia, here. Basically, an ‘Easter egg’ is a hidden message or feature, tucked away somewhere in the system, just waiting for someone to find it.

So we could imagine a wise diviner secreting away extra connections between changing lines and their destinations, ready for us to dig up 3,000 years later, but we don’t have to. It could simply be that these hidden gems are an intrinsic property of the book. The Yi’s made of solid truth, all the way through, and – naturally – it shows.)