Here’s Wikipedia’s definition of a ‘culture hero’:

A culture hero is a mythological hero specific to some group (cultural, ethnic, religious, etc.) who changes the world through invention or discovery.

Chinese mythology seems to be especially full of these: people who are recognised as heroic because they invented millet farming, or writing, or sericulture, not for minotaur-slaying or fleece-fetching.

However, the Dazhuan (the Great Treatise, Wings 5 and 6 of the Yijing) tells its ‘culture hero’ stories differently. Shen Nong, for instance, the Divine Husbandsman who invented ploughing:

‘Shaping wood to make plough-shares and bending wood to make plough-handles, he taught all under heaven the benefits of ploughing and tilling. This may have come from Increase.’ (Hexagram 42)

Richard Rutt, Zhouyi

Or as R.J. Lynn translates, ‘He probably got the idea for this from the hexagram Increase.’

The same formula is used to describe the invention of nets, markets, boats, ox-drawn carts, fortifications, pestle and mortar, archery, houses, formal burial and written records. Sages, named or unnamed, may have introduced the practice, but they ‘probably got the idea for this’ from a hexagram: the Yi is the real hero.

Human wisdom isn’t so much a matter of coming up with ideas, as being able to grasp patterns in the natural world. The first to do so is Fuxi:

‘When Fuxi ruled the world, he looked up and observed the figures in heaven, looked down and saw the model forms under heaven. He noted the appearances of birds and beasts and how they were adapted to their habitats, examined things in his own person near at hand, and things in general at a distance. Hence he devised the eight trigrams with power to communicate with spirits and classify the natures of the myriad beings.’

Rutt, Zhouyi

There is a whole world of mystery in that ‘hence’!

In the examples that follow, this story of discovery goes in reverse: Fuxi went from the real world to the gua; thereafter, we go from the gua to real-world inventions. As Wilhelm says,

‘This chapter tells us how all the appurtenances of civilisation came into existence as reproductions of ideal, archetypal images. In a certain sense this idea contains a truth. Every invention comes into being as an image in the mind of the inventor before it makes its appearance in the phenomenal world as a tool, a finished thing.’

Wilhelm/Baynes Book II (p329)

I don’t think the Dazhuan authors believed that the images originated in the mind of the inventor, though. The hexagram comes first, and the hexagrams arise from nature.

The stories

These ‘culture hero’ stories are told in historical sequence. First Fuxi, then Shen Nong, and then his successors, and finally the unnamed ‘later sages’ whose inventions are contrasted with life in ‘earlier times’. They introduced –

- nets for hunting (30)

- ploughs (42)

- markets (21)

- boats (59)

- carts (17)

- fortifications (16)

- pestle and mortar (62)

- bow and arrow (38)

- roofed houses (34)

- double coffins (28)

- written documents (43)

With our modern knowledge, we might quibble that the pestle and mortar came earlier, but overall this order makes sense: hunting comes before farming, boats before wheels, fortifications before archery, and the written records of a civilised government last of all.

(If there’s any pattern in the choice of hexagrams, though, I can’t find it.)

Sources

All the quotations below come from Richard Rutt’s translation. Although his book is titled only Zhouyi, it’s actually one of the very few I Ching books to contain a full translation of all the Wings – and here, you can read through them as a continuous text, uninterrupted by commentary. I do think this is the best way to encounter them to start with.

R.J. Lynn also includes a full translation of all the Wings. For the Dazhuan, the interspersed commentary isn’t by Wang Bi but one Han Kangbo, who frankly doesn’t seem to have been the brightest spanner in the toolkit. However, Lynn also includes his own end notes, which are excellent. And so too – naturally – is Wilhelm‘s interspersed commentary, even if sometimes the nuclear-trigram-based ideas seem a bit far-fetched to me.

Anyway, here are all the stories, the commentary ideas and some added notes, so you can form your own impressions.

30, Clarity

‘He (Fuxi) twined cords to make nets for hunting and fishing. This may have come from Li.’ (Hexagram 30)

The shape of Hexagram 30, Clarity, does resemble a net:

Wilhelm notes that li, the name of the hexagram, can also mean being trapped, as in a net. (It may be used in this sense in 62 line 6: my book has ‘flying bird leaves’, but Rutt has ‘a flying bird is netted.’)

The culture hero stories start here in the very earliest times, with the same Fuxi who originally observed and discovered the trigrams. This makes me think that he’s the inventor of a net of concepts that captures the whole world and creates Clarity through its patterns.

42, Increase

‘Shaping wood to make plough-shares and bending wood to make plough-handles, he taught all under heaven the benefits of ploughing and tilling. This may have come from Yi‘ (Hexagram 42)

This invention-discovery is attributed to Shennong, the Divine Husbandsman. (You can read more about him here.) This hexagram connection – with Hexagram 42, Increase – can also be explained by the shape of the hexagram as a whole: the top two lines are the hands and handle, three yin lines the curving shaft, and line 1 the ploughshare.

The actions of the two trigrams are a good fit, too: penetrating into the earth (upper trigram xun) and moving it (lower trigram zhen). Wilhelm also points out that both these trigrams are associated with the wood element.

And, of course, the plough brings an Increase in yield – the kind of provision that makes it ‘fruitful to have a direction to go, fruitful to cross the great river.’ (You get much the same idea in the Oracle of Hexagram 26, Great Taming: successful farming is not an end in itself, but a springboard to a different level of achievement.)

21, Biting Through

‘He (Shennong) had markets held at midday, bringing all people under heaven together and assembling all commodities under heaven. They bartered and returned home, every one having got what he wanted. This may have come from Shike.’ (21)

The inspiration here is said to have come from the trigrams: thunder below as the bustle of marketplace activity, and fire above as the sun at midday. Wilhelm adds the nuclear trigrams to the mix: lines 2,3 and 4 make gen, mountain, which also means ‘small paths’, and 3, 4 and 5 make kan, flowing water. Hence we have ‘movement under the sun, a streaming together.’

This really doesn’t feel like a complete explanation, and so Wilhelm also mentions homophones that mean ‘food and merchandise’ and concludes, ‘Evidently the hexagram formerly had the secondary meaning of market.’

I don’t think this ‘secondary meaning’ is very far away from the one we know. Biting Through means bringing things together so they work (‘Biting Through means uniting,’ says the Sequence), and overcoming any obstacles in the way. Isn’t that exactly what a successful market does? You have goats and need pots; I have more pots than I know what to do with, but I’m stumped for lack of a goat. Get through the barriers, bring us together, and everything will work as it should.

Interlude: change

Then follows an interlude that refers to Hexagram 14, line 6:

‘They [the Yellow Emperor, Shao and Yun] allowed things to undergo the free flow of change and so spared the common folk from weariness and sloth. With their numinous powers they transformed things and had the common folk adapt to them. As for change [Yi], when one process of it reaches its limit, a change from one state to another occurs. As such, change achieves free flow, and with this free flow, it lasts forever. This is why “Heaven will help him as a matter of course; this is good fortune, and nothing will be to his disadvantage.”‘

Lynn

Trying to understand this passage, and why it’s inserted here, I’ve been helped by this article by Michael Puett, about a chapter of the Huainanzi (pre-139BC) – see especially the excerpt on page 179. It tells much the same story as this passage of the Dazhuan, of people in ancient times suffering from their primitive way of life,until sages invented homes, clothing, ploughs, boats and carts, and so on.

In the Huananzi, apparently, this story illustrates how the sages don’t just model society on the past – that would be ineffective; instead, they create ‘by following cosmic patterns’ according to the needs of the present. ‘If you understand from whence standards and order arise,’ says the Huainanzi, ‘then you can respond to the times and change.’

The Dazhuan authors, writing about the Change Book, seem to have the same idea: that sages help the people by perceiving a present need and creating change in response. And what better to describe the present moment and the changes it calls for than a hexagram?

59, Dispersing

‘They hollowed out tree-trunks to make boats and shaved wood to make oars. The benefit of boats and oars was ability to reach distant places by crossing unfordable waters, which was profitable for all under heaven. This may have come from Huan.’ (59)

You can see how the idea of boats ‘comes from’ the trigrams of Dispersing: wood above, water below. You might also see the hollowed-out shape of the boat in the enclosed space created by the yin lines 3 and 4, inside yang lines 2 and 5. With this, it will be ‘fruitful to cross the great river,’ as the Oracle text says.

Then again, you might also remember that the Tuanzhuan uses the same logic to describe Hexagram 61, Inner Truth, as a hollowed-out log, and account for ‘crossing the great river’ in its Oracle – and its perfect symmetry makes it a more convincing picture of a boat.

So why was Hexagram 59 nominated as the culture hero? I would imagine this is partly because the inner trigram kan is more perilous than dui, the lake, and a better fit for ‘crossing unfordable waters’, and mostly because Dispersing as a whole is a much more mobile, less stable hexagram, better for ‘reaching distant places’.

17, Following

‘They tamed oxen and yoked horses to transport heavy goods over great distances, benefiting all under heaven. This may have come from Sui.’ (17)

This is one story where the connection to the hexagram seems simple: the cart Follows the horse (or the ox). But naturally people have found more complex reasons why it fits: the upper trigram dui is associated with speech, and lower zhen with movement, so here are human commands leading the draft animals forward. Or (Wilhelm’s version) here are lively, happy animals in front, and the cart moving behind.

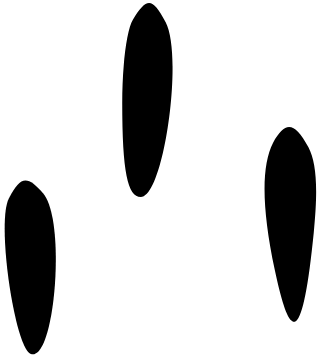

I think the hexagram as a whole –

looks not unlike the horns of the ox at the front (line 6) with the empty wagon (lines 1-4) following behind. If hexagrams 42 and 30 can be pictures of their inventions, why not this one too?

16, Enthusiasm

‘They made defensive double gates and watchmen’s clappers to keep off marauders. This may have come from Yu.’ (16)

How can Enthusiasm inspire the invention of fortifications and defences? Trigrams come to the rescue: the inner trigram kun, earth, also represents a ‘closed door’, and outer trigram zhen, thunder, the action of the watchmen’s clappers. Wilhelm adds the nuclear trigrams: lines 2,3,4 make gen, mountain, another door trigram – hence doubled gates – while line 3,4,5 make kan, a thief.

I find this a bit thin, but I don’t have any better suggestions. Hexagram 16 means anticipation and imagination, and that can be stretched to suggest preparation, and hence defences – but in my experience of the hexagram, it’s more likely to be building castles in the air than manning the battlements against possible attacks. Maybe I’m just too sunny and optimistic by nature…

62, Small Exceeding

‘They cut wood to make pestles and dug hollows in the ground to make mortars. Pestle and mortar were beneficial to all people. This may have come from Xiaoguo.’ (62)

The trigram picture of Hexagram 62, Small Exceeding, shows thunder above the mountain: the pounding pestle and the still mortar, with their two hard surfaces meeting at the center in lines 3 and 4. It’s the perfect contrast with Hexagram 27: thunder below the mountain, moving lower jaw and still upper jaw, drawing a picture of a toothy grin. And Wilhelm also points out that the elemental associations of these trigrams show wood above stone.

Hexagram 62 is ‘Small Exceeding’ or more literally ‘Small Crossing-Over-The-Line’: small transition. Wilhelm suggests this is the transition from eating whole grains to baking, but I’d rather imagine it as a transition for the small, for the grains –

It’s also true that grinding grain is ‘small work’ – a daily household task, nothing grand. The sage who devises pestle and mortar is paying attention to the small details of life, wholly in the spirit of Hexagram 62.

38, Opposing

‘They strung wood to make bows, and sharpened wood to make arrows. The benefit of bows and arrows is keeping all under heaven in awe. This may have come from Kui.’ (38)

Hexagram 38 is Opposing – something that might call for weapons. (It seems to at line 6, after all, until we recognise our future allies and relax the drawn bow.) Still, why bow and arrow in particular?

The trigrams are not so much help this time. We have li, fire, above dui, the lake, with nuclear trigrams kan above li. Kan is danger, li is weaponry, and dui is joy, so Wilhelm ingeniously conjures up a picture of danger contained by weapons (with the two li trigrams on either side of it), so that people are unafraid. We could also say that the fire on the outside is what’s used to harden the arrow-heads. (Squint a little, and might lines 2-5 look like the arrow – line 4 – in the fire?)

And this is all very well, except that there are no trigrams here associated with wood, and nothing to suggest the other half of the invention, stringing the bow. (Dui means splitting and breaking open, not attaching.) Also, Hexagram 38 isn’t particularly about fearlessness, and there’s nothing in the trigrams to say why these weapons should be bows and arrows and not, say, spears and axes.

However, if we take a step or two back, there might be a forest in amongst all these trees. Fire rises up and water sinks down: these two trigrams pull apart. So you could say that they give you (or the sages of earlier times) the idea that if things are attached together and yet pulled in opposite directions, that tension could be powerful. ‘This may have come from Kui‘ after all.

34, Great Vigour

‘In earliest times, men lived in caves or dwelt in open country. Later sages changed this, building houses large and small. A ridgepole at the top and spreading eaves below warded off wind and rain. This may have come from Dazhuang.’ (34)

What’s the source for this inspiration?

It could be the trigrams: the house endures below (inner trigram qian, heaven, that lasts forever) while the thundery weather rages above. Wilhelm adds that the upper nuclear trigram is dui, lake, for rain.

It could be the shape of the hexagram…

… especially if you imagine those two yin lines as they might originally have been written, as the character for ‘8’, ba, 八, it does look something like a roof.

Wilhelm also says that the four strong lines make a ridgepole (just as in the oracle of Hexagram 28) – though since the ridgepole is supposed to be above the eaves, this is all getting a bit confused.

And it can also be from the overall significance of the hexagram: the assertive power of standing firm and not Retreating. Building our own shelters, we’re no longer confined to caves; we can establish ourselves anywhere.

28, Great Exceeding

‘In earliest times burial was performed by covering the corpse thickly with brushwood and laying it in open country with neither mound nor grove; nor were there fixed times for mourning. Later sages changed this, introducing double coffins. This may have come from Daguo.’ (28)

Another hexagram picture: the hard, solid double coffin in the four central lines, with two lines of loose earth around it:

Also, those four yang lines make qian twice over, another doubling. (Wilhelm also says the dead are entering – xun – into the earth and made glad – dui. I find that less persuasive!)

What really grabs my attention here is the contrast with Hexagram 62, Small Exceeding. That inspired the pestle and mortar, a small, everyday transition and change of state for the small grains; this brings the Great Crossing-Over.

43, Deciding

‘In earliest times, knotted cords were used in administration. Later sages changed this, introducing written documents and bonds for regulating the various officials and supervising the people. This may have come from Jue.’ (43)

Here’s civilisation’s crowning achievement, writing. The trigrams encapsulate this: dui on the outside, words and communication, sustained by the enduring power of qian.

This trigram picture is in perfect accord with the Oracle, where the intense energy of that first announcement in the king’s chambers spreads outward to the whole town and beyond.

Can we use this in readings?

Wilhelm is quite clear that these stories are part of a separate tradition, one that had different meanings for the hexagrams. I can see why.

There are a few specifics I might use. Hexagram 30 for me is all bound up with the idea of having a ‘net’ of concepts to think in; the other day I suggested the wisdom of putting things in writing to a querent who had Hexagram 43. (She’d already thought of it.) I particularly like the idea that you can expect the help and protection of heaven in 14.6 to show up not as stability, but as ‘the free flow of change’. But I honestly can’t find any reading examples where it would have helped to think – for instance – of Hexagram 62 as a pestle and mortar, 28 as a coffin or 16 as doubled gates.

And yet… if I take a few mental steps back and let these stories slip into soft focus, it does seem possible to sense connections, and get a more rounded sense of the hexagram meanings. All we can do is try these things out: hold them loosely in mind as we listen to each reading, and see what emerges.