Clarity,

Office 17622,

PO Box 6945,

London.

W1A 6US

United Kingdom

Phone/ Voicemail:

+44 (0)20 3287 3053 (UK)

+1 (561) 459-4758 (US).

.

.I have also found a very nice overview in the philological terrific translation with commentaries of I have also found a very nice overview in the philological terrific translation with commentaries of Dennis Schilling on page 919 - I can only hope that this gigantic work will be translated into English one day. on page 919 - I can only hope that this gigantic work will be translated into English one day.

I feel very uncomfortable with national categorizations. Especially when looking at history and the fruits of national thinking 100 years ago...

Zhuxi, while contributing much, also just made lots of stuff up, including his method of reading multiple lines (and including the yarrow stalk method that's used today).

I would suggest ignoring the unchanging lines as far as divination goes.

the most important stage is a full understanding of the core meaning and then apply any moving lines to that meaning, carefully.

>

>So the question is, How does one justify taking text explicitly reserved for a changing line and nevertheless applying it to an unchanging line?]

As the lines must be either whole or divided, technically called strong and weak, yang and yin, this distinction is indicated by the application to them of the numbers nine and six. All whole lines are nine, all divided lines, six.

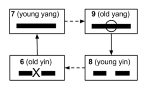

Two explanations have been proposed of this application of these numbers. The Khien trigram, it is said, contains 3 strokes (☰) and the Khwan 6 (☷). But the yang contains the yin in itself, and its representative number will be 3 + 6 = 9, while the yin, not containing the yang, will only have its own number or 6. This explanation, entirely arbitrary, is now deservedly abandoned. The other is based on the use of the 'four Hsiang,' or emblematic figures (<> the great or old yang, <

> the young yang, <

> the old yin, and <

> the young yin). To these are assigned (by what process is unimportant for our present purpose) the numbers 9, 8, 7, 6. They were 'the old yang,' represented by 9, and 'the old yin' represented by 6, that, in the manipulation of the stalks to form new diagrams, determined the changes of figure; and so 9 and 6 came to be used as the names of a yang line and a yin line respectively. This explanation is now universally acquiesced in. The nomenclature of first nine, nine two, &c., or first six, six two, &c., however, is merely a jargon; and I have preferred to use, instead of it, in the translation, in order to describe the lines, the names 'undivided' and 'divided'.

Clarity,

Office 17622,

PO Box 6945,

London.

W1A 6US

United Kingdom

Phone/ Voicemail:

+44 (0)20 3287 3053 (UK)

+1 (561) 459-4758 (US).