Clarity,

Office 17622,

PO Box 6945,

London.

W1A 6US

United Kingdom

Phone/ Voicemail:

+44 (0)20 3287 3053 (UK)

+1 (561) 459-4758 (US).

‘Darkening of the light during flight.

He lowers his wings…’

(Wilhelm/Baynes)

‘A crying pheasant, flying on drooping wing.’

(Rutt)

‘He penetrates the left side of the belly.

One gets at the very heart of darkening of the light.’

(Wilhelm/Baynes)

‘Entering the left flank, finding the crying pheasant’s heart.’

(Rutt)

‘Darkening of the light as with Prince Chi’

(Wilhelm/Baynes)

‘Jizi’s crying pheasant.’

(Rutt)

“The Wilhelm-Baynes translation as “Darkening of the Light” is poetic, but clearly incorrect. …This cannot have been the early meaning because, as emphasized previously, there is no evidence for trigram correlations before the Zuozhuan and Ten Wings.”

‘Brightness hidden, wounded in the left thigh.

For rescue, use the power of a horse.

Good fortune.’

‘Not bright, dark.

At first rises up to heaven,

Later enters into the earth.’

It is hard to see what it would signify yes. And if it doesn't signify anything very much then how much use was it for the language of the oracleHard to believe it could have much significance as an omen unless the Chinese kind does it much less often.

I like the idea they were creating a language although sadly here it isn't one we know the meaning of. A crying pheasant doesn't somehow signify anything to me.They did not set out to convey information to their listeners or readers about either pheasants or wounded light: they were creating a language for an oracle to communicate in.

....seem tentative, not very strong. That may be because pheasants in the UK just screech at anything as you say and so I struggle to connect with the pheasant image because it doesn't seem to mean much. Or rather the meaning is so distant and tentative it isn't a robust meaning. I still don't see where a pheasant fits into the meaning of 36. I guess you did say the golden pheasant was hard to find but then so are many birds.Rutt quotes songs where the pheasant is calling for its mate, and connected with an abandoned lover. Also a case where a pheasant calling at a royal sacrifice was a sign it had been badly done. Not a good sign overall, then.

On her website LiSe gives an alternative for "calling pheasant":It’s been re-translated: ming 明 means ‘pheasant’; yi 夷 means ‘calling’.

with the story:Mingyi can be a pheasant, but it can also allude to the golden colored raven which carries the sun.

Ravens squawk constantly and, combined with the story LiSe gives, it is also possible that in H36 it is not a pheasant but a raven.Long ago there were 10 suns, one for each day of the 10-day week. They would rise in succession, until one day all ten came up together. The earth got scorched, but Hou Yi, Lord Yi, shot down 9 of them and saved the earth from incineration.

...

Ideogram of the hexagram name: the first (upper) character is sun + moon: brightness. The second character is an image of an archer with a string arrow. According to other sources a kneeling archer, aiming his arrow. It means level, smooth, wounding or barbarian (which is anyone 'not us'), but it is also the name of the East tribe, the tribe of the famous archer 夷羿 Yí Yì (Yí of Yì) or 后羿 Hòu Yì (Lord Yi), who shot down the 9 surplus suns.

But there is absolutely nothing to do with a pheasant in an interpretation of 36 is there? Translation by itself doesn't offer interpretation just presents us with pheasants and such and leaves it there.if you look at the work of almost any of the translators who concentrate on recapturing the original, Bronze Age meaning of the text, this simple, relatable picture more or less disappears. Originally, it seems, the hexagram name didn’t mean ‘Brightness Hiding’ at all, but

- Crying Pheasant (Rutt)

- The Calling Arrow-Bird (Field)

- Pelican Calling (Minford book 2)

- Calling Pheasant (Redmond)

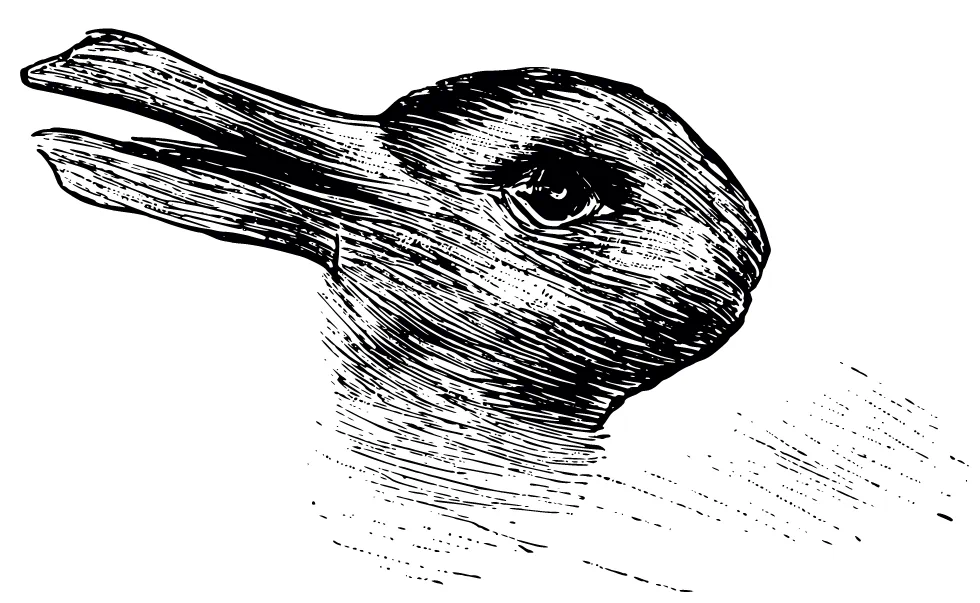

But yes if it's a pun or wordplay well, I don't know because the thing with puns is they are so specific to time and place. Above I just wrote without even thinking 'but the bottom line is' which isn't a pun or really wordplay but is just a common way of saying 'fundamentally' or rather 'it comes down to this' ..something like that...but why we say 'bottom line' I don't know and probably non English speakers wouldn't learn that in lesson 1.Since Chinese is so good at wordplay in general, the Yijing text is probably full of duckrabbits I know nothing about. But isn’t it apt that this hexagram – with its play of lighting-up and hiding – should be one?

What exactly do you mean with "it is it's not something I could use in readings because it doesn't mean much"?I suppose for me the bottom line is (no pun intended) whatever bird it is it's not something I could use in readings because it doesn't mean much.

What I said, the image of a calling bird doesn't connect for me with the story of Prince Ji in the tyrant's court. That carries the greatest meaning for me in 36. A pheasant appears random and so I imagine is connected with wordplay perhaps in a way not yet known. There is no pheasant being used in the text of the Oracle or the lines in any of the translations used in the RJ. the translations I use the most. The fact that the lower trigram is light isn't enough to conjure pheasants of ravens for me. Not to say they aren't there, I mean Hilary's said all these translators uncovering Bronze Age meanings do include itWhat exactly do you mean with "it is it's not something I could use in readings because it doesn't mean much"?

The golden raven (or three legged crow), the pheasant, the phoenix are all (mythical) birds associated with the sun and trigram Fire.

Good Grief Minford has a pelican, I have no idea what they sound likeif you look at the work of almost any of the translators who concentrate on recapturing the original, Bronze Age meaning of the text, this simple, relatable picture more or less disappears. Originally, it seems, the hexagram name didn’t mean ‘Brightness Hiding’ at all, but

- Crying Pheasant (Rutt)

- The Calling Arrow-Bird (Field)

- Pelican Calling (Minford book 2)

- Calling Pheasant (Redmond)

Li "............ The Clinging acts in the pheasant...." (Wilhelm/Baynes, Shuo Kua, Ch. III, 8), the lower trigram. Could this attribute from the Ten Wings have been the source for some author's translation?

Li "............ The Clinging acts in the pheasant...." (Wilhelm/Baynes, Shuo Kua, Ch. III, 8), the lower trigram. Could this attribute from the Ten Wings have been the source for some author's translation?

(from https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/barbarian)From Middle English barbarian, borrowed from Medieval Latin barbarinus (“Berber, pagan, foreigner”), from Latin barbaria (“foreign country”), from barbarus (“foreigner, savage”), from Ancient Greek βάρβαρος (bárbaros, “foreign, non-Greek, strange”), possibly onomatopoeic (mimicking foreign languages, akin to English blah blah). Cognate to Sanskrit बर्बर (barbara, “barbarian, non-Aryan, stammering, blockhead”).

Clarity,

Office 17622,

PO Box 6945,

London.

W1A 6US

United Kingdom

Phone/ Voicemail:

+44 (0)20 3287 3053 (UK)

+1 (561) 459-4758 (US).