Clarity,

Office 17622,

PO Box 6945,

London.

W1A 6US

United Kingdom

Phone/ Voicemail:

+44 (0)20 3287 3053 (UK)

+1 (561) 459-4758 (US).

‘Being drawn. Good fortune, no mistake.

With truth and confidence, it is fruitful to make the summer offering.’

Hexagram 45, line 2

‘With truth and confidence, it is fruitful to make the summer offering.

No mistake.’

Hexagram 46, line 2

‘The neighbour in the East slaughters oxen.

Not like the Western neighbour’s summer offering,

Truly accepting their blessing.’

Hexagram 63, line 5

‘Being drawn. Good fortune, no mistake

With truth and confidence, it is fruitful to make the summer offering.’

Hexagram 45, line 2

‘True and confident,

And so it is fruitful to make the summer offering.

No mistake.’

Hexagram 46, line 2

‘The second NINE, undivided, shows its subject with that sincerity which will make even the (small) offerings of the vernal sacrifice acceptable.’

‘It helps to think of rank as not just an empty bureaucratic status-label, but in its ideal sense of a true measure of your personal capability. Then this becomes an offering that’s naturally proportional to what you can give – and you can see the connection to Hexagram 15, Integrity. With a completely clear sense of yourself – both your limitations and your potential – you can make a true yue offering. It’s your personal call to the spirits (see the fan yao, 15.2) and you – not any external standard – are its measure.’

From ‘Steps through Hexagram 46‘

‘The neighbour in the East slaughters oxen.

Not like the Western neighbour’s summer offering,

Truly accepting their blessing.’

Hexagram 63, line 5

‘… not like the Western neighbour’s yue offering real-substance receive its blessing’

‘Already across, creating success.

Constancy yields a small harvest.

Beginnings, good fortune – endings, chaos.’

Hexagram 63, the Oracle

‘Maybe increased by ten paired tortoise shells,

Nothing is capable of going against this.

From the source, good fortune.’

‘Maybe increased by ten paired tortoise shells.

Nothing is capable of going against this.

Ever-flowing constancy, good fortune.

The king uses this to make offerings to the supreme being: good fortune.’

Hexagram 41, line 5 and Hexagram 42, line 2

Just reading the above and am afraid don't follow. In Chinese Medicine, I think that the term of Summer refers to a time of plenty. I believe the thinking is that the beginning of summer, is really the carry on of the end of the lean spell of Spring, that all gardeners are aware of, and that the term of Summer, in Chinese thinking, if we can take the Medical Classics as pertinent, refers to a time of plenty. Is it possible that the confusion about if it is Spring/small offering, or Summer/abundance makes it rather impossible to render a translation of the Character Yue, and we should perhaps, in the case of such obvious discrepancies of interpretations, render the understanding from the Hexagram itself, which I always assumed was more meaningful, and impossible to change or misinterpret, than the Characters, and possibly multiple interpretations, that followed on from the Hexagram itself. Does anyone know how to interpret Hexagrams just from the lines themselves.A small offering

The character yue, a ‘summer offering’, is one of those interesting ones that appears three times in the Yi:

Two lines within a hexagram pair, Gathering / Pushing Upward, repeating the same phrase, and then a different reference away at the end of the Sequence. What might be learned from reading these three together?

A summer – or spring – offering

In an age of supermarkets, it may not be obvious to us that spring and early summer are seasons of hardship. The stores you depended on through the winter are running low, and there’s little or nothing yet to eat from the garden or fields. English children would eat the new hawthorn shoots, optimistically named ‘bread and cheese’, to get some greenery. And in ancient China, this was the time for an offering.

I’ve seen yue called both a spring and summer offering; the dictionary tells me it was a spring offering originally, in Xia and Shang times, and became a summer offering for the Zhou. Which is it in the Yi? Rutt and Field say summer; Wilhelm goes to the heart of the matter by simply calling it a ‘small offering’. Whether in spring or summer, you would not have much to spare – but you make the offering anyway. As you begin the work of the farming year, you need the spirits’ support.

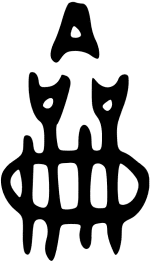

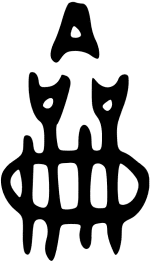

...... yue flute

There are two components to the character yue 禴 . The left-hand side means ‘altar’ and is used to identify words to do with the spirits; the right-hand side, 龠 , shows a double flute. It means both the flute and also an ancient measure of volume. Both of these – the measure and the flute – seem significant.

The measure was a tiny one: around 50ml, say the dictionaries, or 1200 grains of millet. (Did somebody count them?) This is a small offering, from small resources – of plant matter only, without sacrificing animals.

Music (which never runs out) is an important part of the rite, played on this double flute. Many early versions of the character show a single mouthpiece, making it possible to blow into both tubes at once: this flute plays chords, creates harmony by itself. The Shuowen specifies that this is a flute with two tubes and three holes, and that playing it ‘makes it possible to bring all sounds into harmony.’

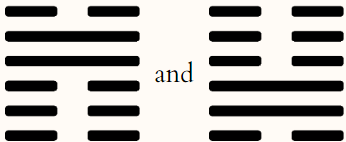

Thinking of this flute – one open mouthpiece, two solid tubes, three open holes – here are the two hexagrams where the word first appears:

View attachment 4965

45.2 zhi 47

‘Drawing’ – the same word as in 58.6 – is 引 yin, and literally refers to drawing a bow: the old character shows a bow and bowstring. Hence it means pulling, attracting and stretching, leading on and encouraging, and drawing out, prolonging.

In theory, this line could just as well be understood in the active voice – ‘drawing’ rather than ‘being drawn’. But line theory gives rise to the idea that this yin second line is ‘being drawn’ by the yang fifth line, and experience agrees. People receive this line when they’re being drawn into involvement, or a relationship, or a course of action, or simply when their attention is being pulled to where it’s needed. This hexagram’s Gathering of energy is exerting a kind of magnetic attraction, ‘drawing’ line 2 outward.

This is good fortune and – a reassurance we need in every line of Hexagram 45 – ‘no mistake’. Why might we think it was a mistake? The clue could be in the zhi gua of the line: 45.2 changes to Hexagram 47, Confining. Its name means oppression, isolation and also poverty. How does Gathering respond to this? With yue, the modest offering made from scarce resources. It will bear fruit provided it’s made with fu: with sincerity, confidence and trust.

‘Being drawn’, you’re under tension because you’re pulled to make this offering – drawn out of your own straitened circumstances to your true relationship with the spirits, and toward your hopes for a good harvest later in the year. Experiences with the line often show this forward and outward pull, towards relationship or deeper connection, or really anything except crouching in the pantry counting how many jars you have left.

46.2 zhi 15

The paired hexagram, Pushing Upward, repeats the same text:

孚乃利用禴

‘Truth, and-therefore fruitful to make (use of) yue.’

No need to be ‘drawn’ here: this is a yang line, part of the growing shoot below the earth in this hexagram’s trigram picture, with its own stored energy ready to push upward and participate at a higher level. The whole hexagram suggests climbing to make an offering at a high place – like the king at line 4, making offerings on (or to) the sacred mountain of the Zhou, Mount Qi.

Spectacular sacrifices are not called for, only small offerings made with an undivided heart. Legge’s translation makes it explicit:

This line points you towards Hexagram 15, Integrity and Modesty, fitting for an unostentatious offering. I wrote about this one some years back:

63.5 zhi 36

The Shang and Zhou were neighbours: the Shang to the East, the Zhou to the west. The Shang were wealthy and powerful, and made ostentatiously grand sacrifices. The Zhou, smaller and poorer, might only manage a small offering, but nonetheless, it’s theirs that receives the spirits’ blessing.

This line joins with Hexagram 36, Brightness Hiding – another story of virtue oppressed by the corrupt Shang regime. But such light is only hidden, never extinguished.

As Harmen points out, there’s an extra character here: not just yue, but yue ji, 禴祭, the summer-offering sacrifice. He suggests this means that only this line refers to the offering; the others mean the musical instrument, which is being played in a different ritual. I think it’s more likely that sacrifice is mentioned here to mark up the contrast with the Western neighbour, who merely ‘slaughter oxen’. The context makes clear that this was for a sacrifice, but the choice of verb seems derogatory: the Zhou perform a named rite from their modest resources, while the Shang seem to think their problems will go away if they just throw enough oxen at them.

I also wonder – and this is pure speculation – whether the character 實 shi, translated ‘truly’, might not be part of the description of the offering. This is the same word as in the Oracle of Hexagram 27 and the second line of Hexagram 50, where it means ‘something real’, substantial and genuine: the vessel contains real substance; you seek something real to fill your mouth. So I think it carries more meaning than just a slight emphasis on ‘receive’.

Looking at this line word-for-word

Are they ‘truly receiving blessing,’ or could this be read as ‘a yue offering of real substance – they receive blessing’?

Also, 實 shi could mean fruit or seed. Fruit is one thing you would not have to offer in spring or summer, of course, but a yue offering of seed?

This line stands at the height of Already Crossing, where we can imagine the Zhou already crossing the river into Shang territory, already founding their dynasty.

The Oracle reminds us of what happened to the Xia and Shang: they began well, but fell into chaos in the end. Beginnings, good fortune: an offering for spring or summer, one that looks forward to the harvest; tiny seeds have more value, more spiritual reality, than full-grown oxen.

Connections?

The references to yue in Gathering and Pushing Upward are obviously connected: the hexagrams are a pair, and the same text is quoted in both. But is there a substantive connection to the quite different text of 63.5 – are we ‘meant’ to remember those lines when we cast this one?

I think we probably are, for a few reasons.

Already Crossing comes at the culmination of the Zhou story and the Yijing Sequence: now, they are crossing the river and taking up the Mandate. At such a time, they need to reconnect with their spiritual roots: the simple, forward-looking offerings, the gathering at the temple and the ascent to Mount Qi.

The lines in 45 and 46 both advise making use of the yue offering; in 63.5, the offering is crowned with ‘receiving blessing’. The earlier lines emphasise the petition, but this one tells the whole story, from petition to response – from Brightness Hiding to blessing. Maybe it’s as if the early offering were not so much asking for a good harvest as expressing trust and gratitude. (Bradford Hatcher’s take on this line: the Shang say ‘please’, the Zhou say ‘thank you’.)

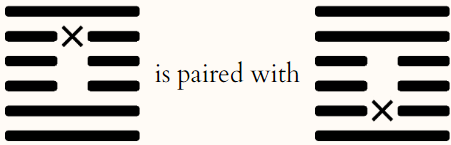

And finally, the line positions. It’s actually a bit odd that those two lines should share the same text, because structurally, they’re not the same line. To clarify…

View attachment 4966

41.5 and 42.2 share text and are paired lines – the ‘same’ line in the hexagram shape, just seen from the opposite perspective. The same is true of 43.4 and 44.3 (‘thighs without flesh, moving awkwardly now’) and 63.3/ 64.4 (stories of attacks on Demon Country): the lines that share text are paired lines.

(The other exception to the rule is 11.1 with 12.1 – but that’s an unusual pair, complementary as well as inverse, so there is a sense in which lines in the same position map onto one another.)

So… why should 45.2 be echoed in the second line of 46, and not the fifth? Perhaps because these two second lines are reaching out all the way to another fifth line, out across the river, and 45.2 is ‘being drawn’ further than we thought.

I shall look at the Harmen Mesker links, thank you.The timing of the yue offering changed, but its nature - small, modest - didn't. There isn't a discrepancy here.

There are methods of interpreting hexagrams without looking at the text, yes. They don't interest me, but have you found your way yet to Harmen Mesker and his Youtube videos and podcasts? He's familiar with Wen Wang Gua and isn't averse to ignoring the text generally. Here's an episode on Wenwanggua.

Excuse me but that is simply incorrect. YinYang is without any doubt the foundations of everything, ot it wouldnt be YinYang. The Yi is derived from the principles of YinYang. The"glorious mixture of imagery, structural relationships, myth and poetry" are part of the ten thousand things, that are built, derived, from YinYang. How can there be any dispute of that fact. The YinYang is not a philosophy, it is a fact, and it is that very fact that makes Chinese Medicine so effective in so many ways. We breathe because of YinYang, there would be no life without YinYang.As in said in the other thread, the Yi is not built on yin and yang. Much more accurate to say that yin and yang have their roots in the Yi. The Yi is built (or just grows) from a glorious mixture of imagery, structural relationships, myth and poetry. Structure and text are interwoven and work together, like bones and flesh. If you ignore either one, you're not consulting the Yi any more. (You wouldn't be yourself without your skeleton, and although looking at it would tell me a lot about you, it isn't you!)

In theory it sounds as though the hexagram structures should be less open to interpretation than text, and should be a way to escape ambiguity. In practice, this just isn't so. The text is uniquely suited to challenging and confronting our assumptions. Someone interpreting from structure alone is a lot more vulnerable to just finding what they set out to look for. At least, that's what I've observed.

If you get right into the technical detail of a system like Wenwanggua, maybe you learn so many rules that the whole process of interpretation becomes entirely mechanical, and ambiguity is no longer an issue? I think that's a lot of its attraction. But from the way Harmen introduces WWG in that video, it seems the wholly mechanical 'insert question, crank gears, get answer' process is a long way from his thoughts.

As Hilary said in the other thread, though, "vapour" and "rock/earth" as objects isn't the right paradigm. It's how they act or can be acted upon.The Hexagram is not an image, as is obvious from the image of the broken and the solid lines, which are totally and completely opposite to the actual meanings. That is set out in Hexagram 1 and 2 so I dont think anyone would be disagreeing with that, Solid Line in the Yi represent the Male, Heaven, the most Yang, a broken line represents the Female, Earth, the most Yin, but the Earth is solid, Heaven is vapour, the complete opposite of what the lines look like.

Yes, and making holes in it and dividing it up is quite tricky, too!Controlling air is harder and more limited.

Sorry but I dont follow. The meaning of Heaven and Earth are not meant in the Yi to be "objects". But the nature of life is that the nature of things is that all are part of a pair, as in Hexagram 1 and 2. The polar opposite of each other, the Heaven and Earth being just one of the possible labels that can be attached to that polarity. In TCM that manifestation includes, in the definitions of YinYang, such things as Blood and Vapour.As Hilary said in the other thread, though, "vapour" and "rock/earth" as objects isn't the right paradigm. It's how they act or can be acted upon.

Earth can be split apart, rain can soak into it, it can be made into shapes, things can be built with bricks made out of it, and so on. Controlling air is harder and more limited. All I can think of that they would have had back then is blowing on somethingor fanning the air.

Dont think I have the hang of this yet, I missed this comment.Yes, and making holes in it and dividing it up is quite tricky, too!

Sorry but I missed this one as well. I am definitely not up to speed yet.About the primacy of yin and yang theory, I think we are talking at cross purposes. I'm referring to the history: the oracle is older than the theory. Your point is more metaphysical. Your belief in the metaphysical primacy of yin-yang theory means that you expect the Yi to fit with it - and people generally find that it does.

About the lines in a cast. They originate as numbers - odd or even. Our convention of writing odd numbers as solid lines and even numbers as broken lines has its origins in writing them as the Chinese numerals 1 and 8. Looked at from that point of view, there's no reason why the way the lines are written should coincide with the concepts of yin and yang.

But as I've tried to show, they actually do. (Another way to see it is just that odd numbers are yang, even numbers are yin, and a broken line is written with two strokes.) Have you read the Dazhuan? That's the one place in the Yijing that yin and yang get a mention, so it would let you go back to an authentic source instead of debating with me. Anyway, I recommend it.

I'm not sure whether this is what you meant by 'equally possible', but the four kinds of line are not equally probable - each line is three times more likely to be stable than moving.

My apologies Hilary. I missed this one as well.I think it would be simpler if you put your TCM knowledge on the back burner for the moment and engaged with the Yi in its own terms. There must be some very interesting comparisons to be made and light to be cast between the two traditions, but... one at a time?

I don't follow. On the first you seem to say that you are talking history, and then immediately saying that history doesn't tell us much.Discussions are what it's for, yes!

Regarding line numbers - once again, you're talking theory, I'm talking history. We don't know the history of how the numbers were originally derived in divination, but you can see in early manuscripts and inscriptions what was written. If you then have a system of thought that says what was written makes no sense... that system of thought obviously wasn't shared by those who wrote the manuscripts. Which brings me back to my suggestion that you learn the Yi on its own terms first.

Here's a page describing how to cast a hexagram with three coins:

This one compares yarrow and coin methods and their odds:

Casting a hexagram

In this part of the course you will... Be introduced to the simple three-coin method of casting a Yijing reading Cast your own first reading, and… …start to connect with and understand itwww.onlineclarity.co.uk

There is no traditional system of casting in which moving lines occur as frequently as unmoving lines, and I really wouldn't recommend that you invent one. It would make for some very hectic, confusing readings.

yarrow or coin

Some history The first users of the I Ching consulted by sorting yarrow stalks – the yarrow being a sacred plant imbued with spiritual power, and thus naturally right for seeking the truth. Later, as the I Ching became more popular and widely used, a simpler method was invented using three coins. Ewww.onlineclarity.co.uk

Sorry I dont understand the question.You're interested in odds are you? Probabilities?

Hilary sent me a link to a probability section of the siteSorry I dont understand the question.

I think it would be better to study and understand the tradition before dismissing it.Is it not for us who are alive and using the Yi, to evaluate if what those that wrote the manuscripts were correct, or not.

A small offering

The character yue, a ‘summer offering’, is one of those interesting ones that appears three times in the Yi:

Clarity,

Office 17622,

PO Box 6945,

London.

W1A 6US

United Kingdom

Phone/ Voicemail:

+44 (0)20 3287 3053 (UK)

+1 (561) 459-4758 (US).