Clarity,

Office 17622,

PO Box 6945,

London.

W1A 6US

United Kingdom

Phone/ Voicemail:

+44 (0)20 3287 3053 (UK)

+1 (561) 459-4758 (US).

What is there to tell us to do so?As for the usage of "Forest of Changes",we can translate the Fuxi's trigrams to King Wen's.

| 乾之: | 乾:道陟石阪,胡言連蹇。譯瘖且聾,莫使道通。請謁不行,求事無功。 |

Is it the representation of 乾? So, you need to throw all the book about original Iqing. "道陟石阪" should be translated as "climbing on steep slopes"and"請謁不行" should be translated as "cannot to meet somebody" simply

乾之: 乾:道陟石阪,胡言連蹇。譯瘖且聾,莫使道通。請謁不行,求事無功。

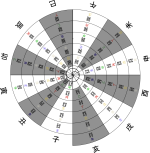

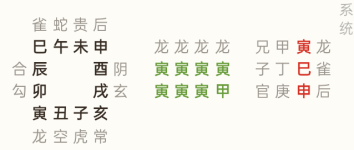

This is very interesting.Do you know how hexagrams mapped to the Chinese Ganzhis(干支)? As you see above. The period it emerged in is Ziue/Dang(隋、唐) dynasty roughly.

I saw in Ni Hua Ching's The Book of Changes and the Unchanging Truth there were some diagrams of the GanZhi's, one of which matched this pattern more or less:According to the formula above, it can be reduced to:

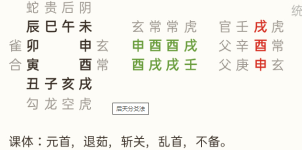

甲子䷁䷗ 丙子䷚ 戊子䷂ 庚子䷩ 壬子䷲ 乙丑䷔ 丁丑䷐ 己丑䷘ 辛丑䷣ 癸丑䷕ 甲寅䷾ 丙寅䷤ 戊寅䷶ 庚寅䷝䷰ 壬寅䷌ 乙卯䷒ 丁卯䷨...辛巳䷍ 癸巳䷪ 甲午䷀䷫ 丙午䷛ 戊午䷱ 庚午䷟ 壬午䷸ 乙未䷯ 丁未䷑ 己未䷭ 辛未䷅ 癸未䷮...

it just likes your Xiantian diagram. No need any diagram of Shao Yong(邵雍).

離之離:時乘六龍,為帝使東。達命宣旨,無所不通。

So, Your 離 represent "driving six dragons"? "時乘六龍" is a original text for 乾 in Iqing.

I think it is just a brilliant idea for preventing someone to read it. So, after two thousand years, 乾 in Forest of Changes still represent "rock slopes" but have not any other views.What I sense here is the concept of the xian tian energies coming through into hou tian.

I think that any books of changes is cannot translated from chinese. I have a divination that:I'm still exploring, will post more as I find greater clarity.

And yet hexagrams are their own language, and a language of interconnected principles.I think that any books of changes is cannot translated from chinese.

I have read that some ideas became threatening to the state, so were destroyed or manipulated or replaced. This would indeed be a brilliant way of hiding a poignant secret. Perhaps if the Fu Xi diagram did exist prior to Shao Yong then it was kept alive in this way. Clearly there is something beneath the surface here.I think it is just a brilliant idea for preventing someone to read it.

So, after two thousand years, 乾 in Forest of Changes still represent "rock slopes" but have not any other views.

And yet it is 52 unchanging in Forest that speaks about the stillness represented by the mountain hexagram.

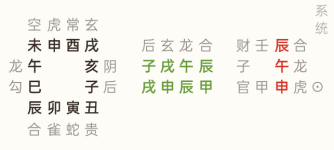

The first time I used 焦氏易林, I take a divination about "郭威(A.D. 9/10/904-2/22/954"). I get the hexgram 1->13. 1->13 in 焦氏易林 is: 子号索哺,母行求食。反见空巢,訾我长息。If I map the 1-13 to 30->21. 30-21 in 焦氏易林 is: 金城铁郭,上下仝力,政平民欢,寇不敢贼。@Thomas6 So far in my readings, it is always the original sequence and not the decoded one that reveals meaning to me. Sometimes it is confusing, but it can be worked out according to my methods of determining whether or not the line should actually be allowed to change. Doing the same with the decoded version does not meet with the same uncanny resonance, though I cannot discount that there may be another way of working with that correlation. I just am working with the one that actually leads to clarity.

The Wuzhen pian says:

You should know that the source of the stream, the place where the Medicine is born,is just at the southwest -- that is its native village.

The southwest is the land of Kun ☷, the place where the Yin culminates and the Yang is born. Lu Ziye said:

The Medicine comes forth in the southwest, the position of Kun;if you wish to seek the position of Kun, how could it be separated from that "man"?I have disclosed the secret in clear words, and you should remember it;but I am afraid that when you meet him, you will not recognize the True.

The name of this man is "man who does not die," or True Man (zhenren). An ancient immortal said:

If you want a man not to die,you must seek the man who does not die.

I cannot understand this kind of philosophical prehension. Because philosophical prehension can described on anything to one's view.When strength gains balance, and is not one-sided or partial, firmness and flexibility match each other. This is like seeing the dragon in the field; the living energy is always there, natural goodness is not obscured, the spiritual embryo takes on form. A great person is one who does not lose the innocent mind of an infant, and is therefore "beneficial to see."

I would say that this line is not being advised to change. The strength is balanced and "the living energy is always there", so we aren't meant to use it up and let it exhaust into becoming yin. Seeing the great person is also a coded saying for seeing the great person that comes to rejoin one through the mysterious gate, which comes of emptiness, kun ☷, the position of the southwest.

I cannot understand this kind of philosophical prehension. Because philosophical prehension can described on anything to one's view.

I do not agree with your view. Chinese classic book alway deliberate a clause and word repeatly. But generally we don't know their literary allusion.The first line doesn't matter much. The last character doesn't matter much either, since it is telling us it is a negative outcome.

I'm speaking loosely for this one poem. I say that it doesn't matter much in this instance, because we have enough to get meaning from that aligns with the yijing line statement. There is a frail person, they are leaving, it is negative.I do not agree with your view.

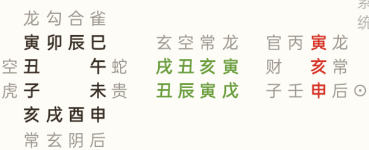

Because I cannot explain it for you. I use 六壬&六爻 to explain Iqing but you may not study them, even you study them and you are a native-born Chinese. I just want to tell you that I-Lin should be decoded. Further, it is my own's method. For example, 乾:I do not see you explaining the meaning in terms of the yijing line statements at all to argue that the Forest should be decoded differently

Thanks! I'll explore this more when I am able to interpret from the perspective of the Liu Ren.But I can share my divination examples using I-Lin.

☰元(天、魁)

☱睪(澤,皋)

☲至(否、㔻、丕)

☳辰(震、振、辰、阵、陈、东、瞰)

☴丰(风、封、豐)

☵兑

☶干(乾、榦)

☷复(覆穴、復、闭)

Clarity,

Office 17622,

PO Box 6945,

London.

W1A 6US

United Kingdom

Phone/ Voicemail:

+44 (0)20 3287 3053 (UK)

+1 (561) 459-4758 (US).